4.2 Data-Level Parallelism and SIMD

Data-Level Parallelism (DLP) is a parallel computing strategy focused on executing the same operation on multiple distinct data elements simultaneously. This paradigm is formally realized in hardware through Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) architectures.

Definition: Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) A class of parallel computers in Flynn’s taxonomy. It describes computers with multiple processing elements that perform the same operation on multiple data points simultaneously. Thus, such machines exploit data-level parallelism.1

For computational tasks characterized by high data volume and repetitive operations—such as linear algebra, image and signal processing, financial modeling, and physics simulations—SIMD offers a performance advantage over scalar (one-operation-per-instruction) processing. A scalar processor must iterate through a loop, whereas a SIMD-capable processor can operate on a vector of data in a single instruction cycle.2

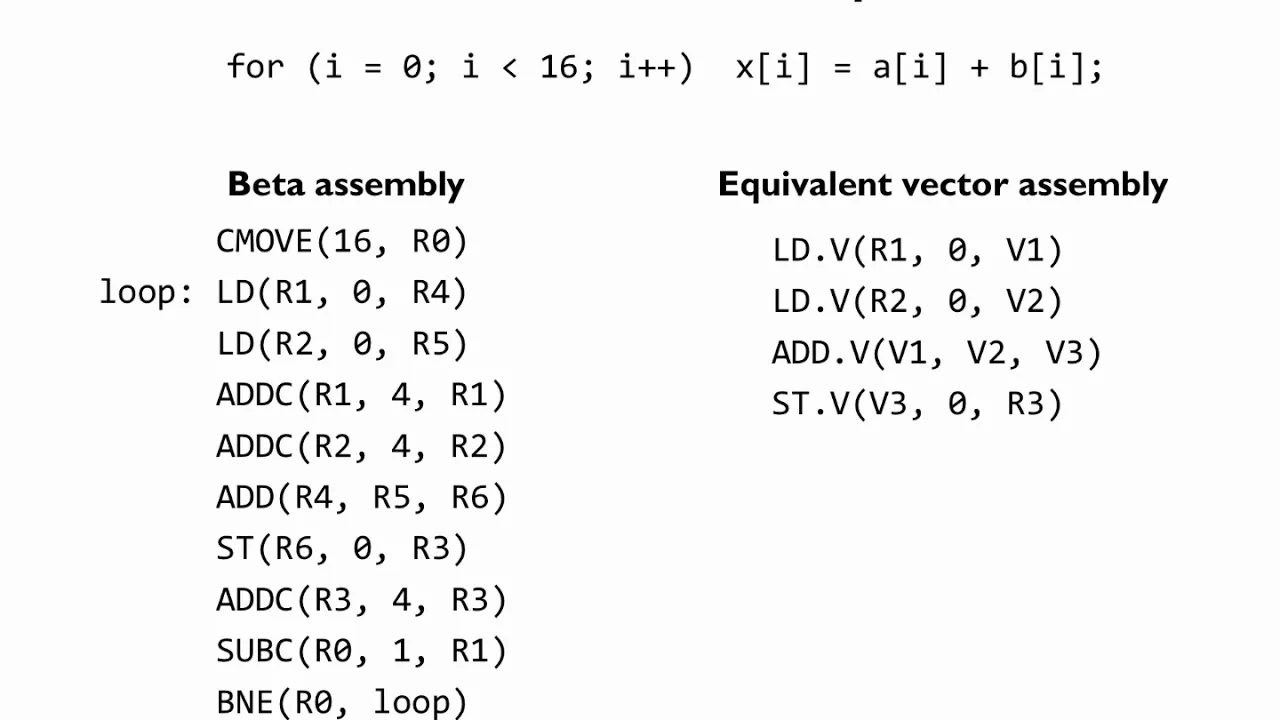

An example of Data-Level Parallelism. The scalar implementation requires a 10-instruction loop to process 16 elements, while the equivalent vector implementation requires only 4 instructions. Credit: MIT OpenCourseWare.3

The evolution of SIMD within the x86 instruction set architecture (ISA) is a progression of increasing vector width and architectural refinement, driven by the demands of graphics, scientific computing, and artificial intelligence.

Early x86 SIMD: MMX

Section titled “Early x86 SIMD: MMX”Intel introduced the first mainstream x86 SIMD extension, MultiMedia eXtensions (MMX), in 1996. MMX was designed to accelerate the performance of multimedia applications.

- Vector Width: 64-bit registers.

- Data Types: Packed integers (e.g., eight 8-bit integers, four 16-bit integers).

- Target Applications: Basic image manipulation, audio codecs, and 2D/3D games.

However, the implementation of MMX involved an architectural compromise that limited its adoption.

Case Study: The MMX and FPU Conflict

Section titled “Case Study: The MMX and FPU Conflict”To reduce implementation cost, the 64-bit MMX vector registers were not new, independent hardware registers. Instead, they were aliased onto the existing 80-bit x87 Floating-Point Unit (FPU) registers.

- The Problem: This created a conflict. A program could not execute MMX and floating-point instructions concurrently. Switching between the two modes required an explicit

EMMS(Empty MMX State) instruction, which incurred performance overhead by flushing the MMX state.4 - The Impact: This penalty discouraged adoption by developers, as many applications (especially in 3D graphics) needed to interleave floating-point calculations for geometry with integer-based operations for texture mapping and pixel manipulation. This is an example of how architectural compromises can limit a feature’s utility.

The SSE Era: General-Purpose SIMD

Section titled “The SSE Era: General-Purpose SIMD”In 1999, Intel launched the Pentium III processor with Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE), a redesigned implementation of SIMD that addressed the limitations of MMX.

- Architectural Separation: SSE introduced a new, dedicated register file with eight 128-bit registers (XMM0-XMM7), independent of the FPU stack. This eliminated the MMX/FPU conflict and allowed for interleaving of scalar, floating-point, and SIMD code.5

- Floating-Point Focus: The initial version of SSE primarily targeted single-precision (32-bit) floating-point operations, enabling one instruction to process four values simultaneously. This was in response to the requirements of real-time 3D graphics.

The introduction of the Pentium 4 processor and its NetBurst microarchitecture in 2000 brought SSE2, an expansion that established SIMD as a general-purpose computing feature.

- Expanded Data Types: SSE2 added a comprehensive suite of instructions for both double-precision (64-bit) floating-point numbers and packed integers (from bytes to quadwords) operating within the 128-bit XMM registers.6

- Generality: With support for high-precision floating-point and a full range of integer types, SSE2 made SIMD viable for scientific and engineering applications, not just multimedia. It rendered the MMX instruction set largely obsolete.

Subsequent extensions incrementally refined the 128-bit SIMD paradigm:

- SSE3 (2004): Added “horizontal” operations (e.g., summing elements within a single vector).

- SSSE3 (2006): Provided more specialized multimedia and signal processing instructions.

- SSE4 (2007): Introduced instructions for dot products, population count, and string/text processing.5

Advanced Vector Extensions (AVX)

Section titled “Advanced Vector Extensions (AVX)”A significant change occurred in 2011 with Advanced Vector Extensions (AVX), which doubled the vector width and enhanced the programming model.

- 256-bit Vectors: AVX introduced new 256-bit YMM registers, which extended the existing XMM registers. This allowed for processing eight single-precision or four double-precision floating-point values at once.

- Three-Operand Instructions: AVX transitioned from a two-operand (e.g.,

A = A + B) to a three-operand, non-destructive format (e.g.,C = A + B). This allows the compiler to preserve source registers, reducing register-copying instructions and improving code generation.7 - AVX2 (2013): Extended 256-bit operations to the full range of integer data types.

The AVX-512 extension, first introduced in 2016, is a key x86 SIMD extension for high-performance computing.

- 512-bit Vectors: Vector width is again doubled to 512 bits (ZMM registers), capable of processing 16 single-precision or 8 double-precision floats per instruction.

- Mask Registers: A key feature is the introduction of “opmask” registers (

k0-k7), which allow for conditional, per-element execution within a vector. This improves the ability to vectorize code containing conditional logic (e.g.,if-then-elsestatements), which was previously a bottleneck.7

Summary of x86 SIMD Evolution

Section titled “Summary of x86 SIMD Evolution”| Instruction Set | Year | Vector Width | Key Features & Architectural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMX | 1996 | 64-bit | Packed integers only. Aliased with FPU registers, causing performance penalties. |

| SSE | 1999 | 128-bit | Dedicated 128-bit XMM registers. Focused on single-precision floating-point. |

| SSE2 | 2000 | 128-bit | Added double-precision FP and comprehensive integer support. Established the foundation for general-purpose SIMD. |

| SSE3/SSSE3/SSE4 | 2004-07 | 128-bit | Incremental additions: horizontal operations, dot products, string processing. |

| AVX | 2011 | 256-bit | Doubled vector width to 256-bit YMM registers. Introduced non-destructive 3-operand instruction format. |

| AVX2 | 2013 | 256-bit | Extended 256-bit support to integer data types. |

| AVX-512 | 2016 | 512-bit | Doubled vector width to 512-bit ZMM registers. Added opmask registers for efficient conditional vectorization. |

References

Section titled “References”Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

“Single instruction, multiple data - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_instruction,_multiple_data ↩

-

Patterson, D. A., and J. L. Hennessy. Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface. Morgan Kaufmann, 2013. ↩

-

“Computation Structures - Part 2: Computer Architecture, Chapter 21: Vector Processing.” MIT OpenCourseWare. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/6-004-computation-structures-spring-2017/pages/c21/c21s2/c21s2v2/ ↩

-

“MMX (instruction set) - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MMX_(instruction_set) ↩

-

“Streaming SIMD Extensions - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streaming_SIMD_Extensions ↩ ↩2

-

“Inside the NetBurst™ Micro-Architecture of the Intel® Pentium® 4…” Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.ele.uva.es/~jesman/BigSeti/ftp/Microprocesadores/Intel/IA-32/Articulos/netburst.pdf ↩

-

“Intel® Instruction Set Extensions Technology.” Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/support/articles/000005779/processors.html ↩ ↩2