3.2 Massively Parallel Processing (MPP)

In the landscape of high-performance computing during the 1980s, a paradigm shift occurred, moving away from the monolithic vector supercomputers towards Massively Parallel Processing (MPP). The MPP philosophy was that computational power could be scaled by using a large number of simple processors, rather than a single, complex processor.1 This section examines the rise of MPP through a case study of a key example: the Connection Machine.

Case Study: The Connection Machine

Section titled “Case Study: The Connection Machine”The development of the Connection Machine at Thinking Machines Corporation (TMC), co-founded by W. Daniel “Danny” Hillis in 1983, differed from the prevailing von Neumann architecture.2 Hillis’s doctoral research at MIT formed the basis for a machine designed for data-parallel computation.1

Defining Data Parallelism

The data parallel model is a programming paradigm in which parallelism is achieved by applying the same operation simultaneously to all elements of a large dataset. Instead of a single processor iterating through the data, the model assigns a simple processing element to each data point, allowing for parallel execution.3 This approach is particularly well-suited for problems with inherent data regularity, such as image processing, scientific simulations, and neural network training.4

To support this model, TMC developed specialized programming languages, including C* and *Lisp, which provided high-level constructs for expressing data-parallel operations, abstracting the architectural complexity from the programmer.1

Architectural Evolution: The Connection Machine Series

Section titled “Architectural Evolution: The Connection Machine Series”The Connection Machine series underwent a significant architectural evolution, reflecting both the maturation of the MPP concept and the changing economics of the microprocessor market.

| Feature | CM-1 (1986) | CM-2 (1987) | CM-5 (1991) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | SIMD | SIMD | MIMD (with SIMD simulation) |

| Processors | Up to 65,536 custom 1-bit processors | Up to 65,536 custom 1-bit processors | Up to 2,048 SPARC RISC processors |

| Floating Point | None | Weitek 3132 FPU per 32 processors | Integrated with SPARC processors |

| Memory | 4 Kbits per processor | 64 Kbits per processor | Up to 128 MB per processor |

| Interconnect | 12-dimensional hypercube | 12-dimensional hypercube | ”Fat Tree” network |

| Peak Performance | N/A | 2.5 GFLOPS (with FPUs) | 131 GFLOPS (1024-node system, 1993) |

CM-1 and CM-2: The SIMD Hypercube

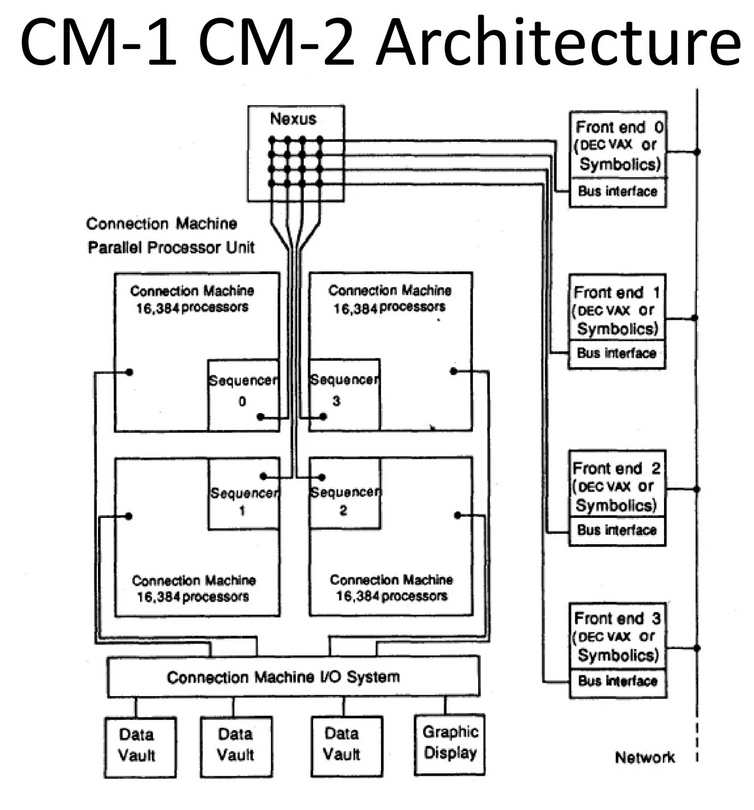

Section titled “CM-1 and CM-2: The SIMD Hypercube”The initial models, the CM-1 and CM-2, were an embodiment of Hillis’s original vision. Both machines utilized the same cubic casing (approximately 1.8 meters per side) and shared fundamental architectural principles.6

Architectural Details

Section titled “Architectural Details”The CM-1 and CM-2 featured several innovative architectural elements:6

- Bit-Serial Processing Elements: Each custom VLSI chip (using 2-micron CMOS) housed 16 1-bit processor cells, requiring 4,096 chips for a full 65,536-processor system.6

- Dual Communication Networks:6

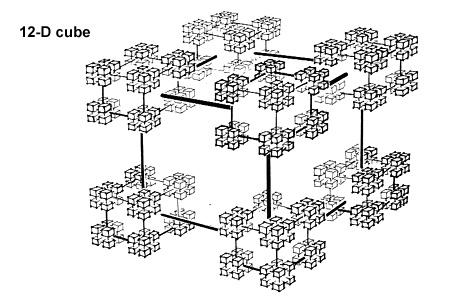

- 12-Dimensional Hypercube Router: Provided general-purpose packet-switched messaging for irregular communication patterns (latency ~700 cycles). Included hardware message combining for reduction operations.6

- NEWS Grid (North, East, West, South): A dedicated 2D mesh for nearest-neighbor communication, approximately 6 times faster than the router for regular data patterns.6

- Virtual Processor Model: Programmers could define data structures with more virtual processors than physical processors. The VP-ratio determined how many virtual processors each physical processor simulated, allowing programs to scale independently of hardware configuration.6

Their key architectural features included:

- Massive Parallelism: A full system contained 65,536 simple, bit-serial processors.

- SIMD Execution: A central sequencer broadcast a single instruction to all processors, which executed it synchronously on their local data. This model was highly efficient for uniform operations across large datasets.

- Hypercube Interconnect: The processors were connected in a 12-dimensional hypercube topology. This network provided high-bandwidth, low-latency communication, with a maximum hop distance of only 12 between any two nodes.7

- Floating-Point Enhancement (CM-2): The CM-2 addressed the CM-1’s computational limitations by integrating Weitek 32-bit floating-point accelerators (FPAs).56 The 1-bit processors handled control, memory access, and data routing, while feeding operands to the FPAs for high-speed arithmetic. This hybrid approach achieved 2.5 GigaFLOPS for 64-bit matrix multiplication and up to 5 GigaFLOPS for dot products.6

- Memory Expansion (CM-2): Memory per processor increased from 4 Kilobits (CM-1) to 64-256 Kilobits (CM-2), supporting total system memory of 512 MB.6

The physical design was a cube composed of smaller cubes, with LEDs indicating processor activity.1

CM-5: Shift to MIMD and Commodity Processors

Section titled “CM-5: Shift to MIMD and Commodity Processors”The CM-5, released in 1991, marked a strategic pivot in response to the rapid performance gains of commodity RISC microprocessors.8 TMC marketed this as a “Universal Architecture,” capable of running both data-parallel and message-passing applications efficiently.9

Architectural Innovations

Section titled “Architectural Innovations”The CM-5 introduced several groundbreaking architectural features:9

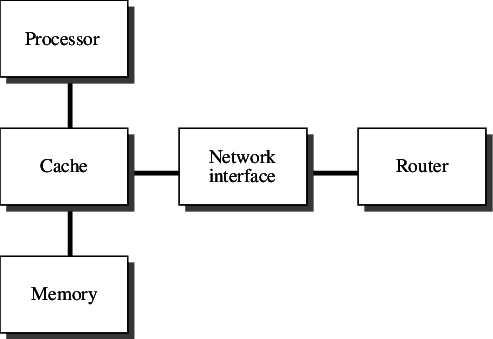

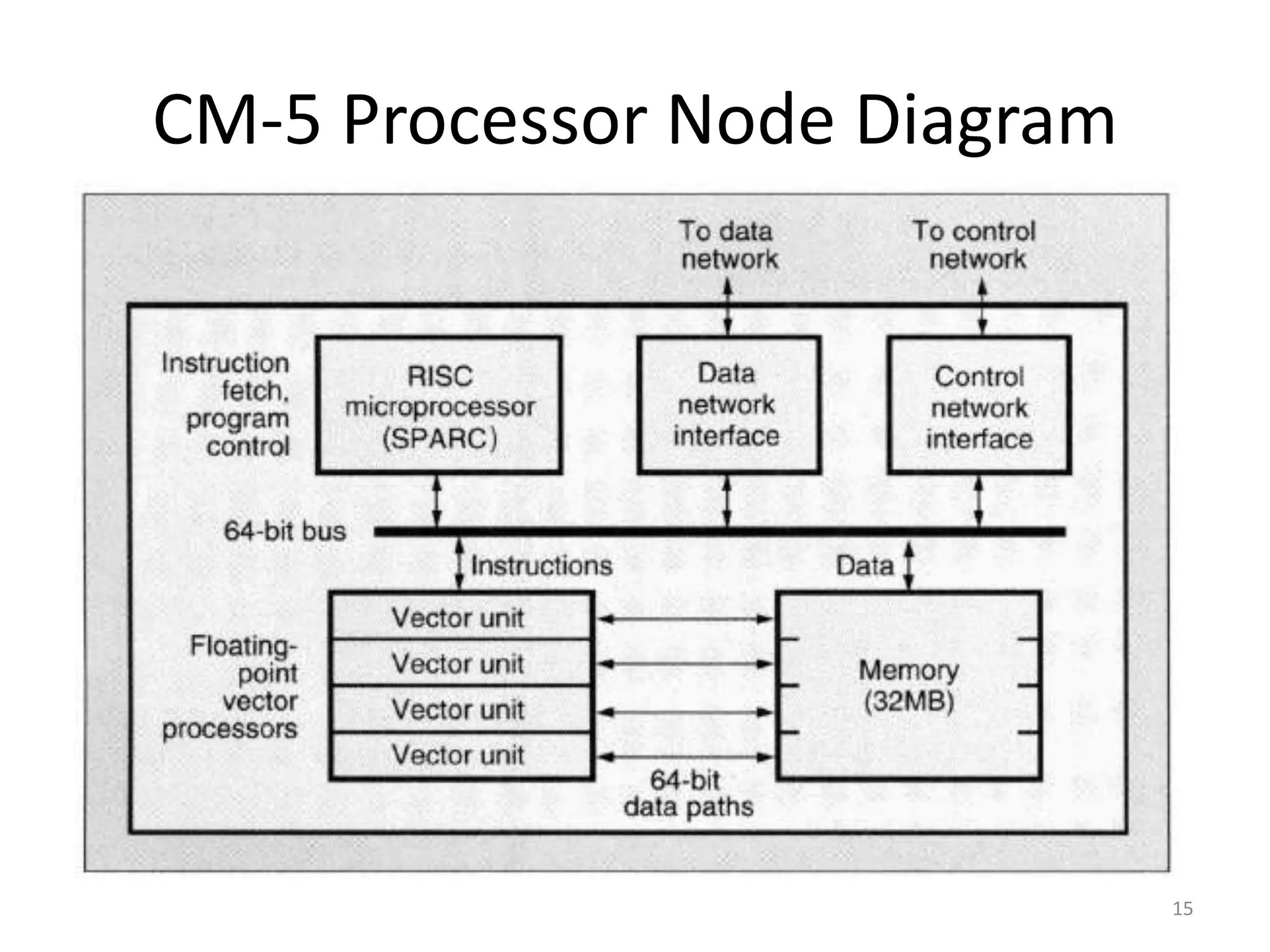

- Processing Nodes: Each node contained:

- Tripartite Network Architecture:9

- Data Network: A 4-ary fat-tree topology with 20 MB/sec leaf bandwidth. Used randomized routing to prevent hot spots and provided scalable bisection bandwidth.9

- Control Network: A binary tree supporting broadcast, reduction, parallel prefix (scan), and barrier synchronization operations in hardware, enabling “Synchronized MIMD” execution.9

- Diagnostic Network: Provided back-door access for system monitoring and fault isolation.9

- Scalable Disk Array (SDA): Storage nodes connected directly to the data network as first-class citizens, utilizing RAID 3 and delivering sustained transfer rates exceeding 100 MB/sec.9

- MIMD Architecture with Data-Parallel Support: The custom bit-serial processors were replaced with hundreds or thousands of standard Sun SPARC RISC processors. Each processor could execute an independent instruction stream, making the system a MIMD machine, yet it could efficiently simulate SIMD behavior for data-parallel codes through the Control Network.59

- Software Ecosystem: The system ran CMost (a SunOS variant) and supported multiple programming models:9

- CM Fortran and C* for data parallelism

- CMMD library for explicit message passing

- Active Messages (developed at UC Berkeley), which reduced communication latency from milliseconds to microseconds9

- Performance Achievement: A 1,024-node CM-5 at Los Alamos National Laboratory achieved 59.7 GFLOPS on the Linpack benchmark, ranking it #1 on the June 1993 TOP500 list.9

Impact and Legacy

Section titled “Impact and Legacy”While Thinking Machines Corporation ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 1994, the Connection Machine series had a significant impact on high-performance computing.

- Demonstration of MPP Viability: The CM series demonstrated that massively parallel architectures could achieve performance comparable or superior to traditional vector supercomputers for certain applications. A CM-5 was ranked the world’s fastest computer in 1993.1

- Popularizing Data Parallelism: It popularized the data-parallel programming model, which remains a key concept in modern parallel computing, particularly in the context of GPUs.

- Influence on Interconnects: The hypercube and fat tree networks led to research and development in high-performance interconnects, a critical component of all modern supercomputers.

- Scientific Applications: CM-2 and CM-5 systems were used to advance research in fields such as quantum chromodynamics, oil reservoir simulation, and molecular dynamics.10

The concepts developed by TMC provided a foundation for subsequent supercomputer designs, demonstrating the viability of large-scale parallelism.

References

Section titled “References”Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Connection Machine - Wikipedia, accessed October 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connection_Machine ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

Thinking Machines Corporation - Wikipedia, accessed October 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thinking_Machines_Corporation ↩

-

Connection Machine® Model CM-2 Technical Summary - Bitsavers.org, accessed October 2, 2025, https://bitsavers.org/pdf/thinkingMachines/CM2/HA87-4_Connection_Machine_Model_CM-2_Technical_Summary_Apr1987.pdf ↩ ↩2

-

The Connection Machine (CM-2) - An Introduction - Carolyn JC …, accessed October 2, 2025, https://spl.cde.state.co.us/artemis/ucbserials/ucb51110internet/1992/ucb51110615internet.pdf ↩

-

Connection Machine - Chessprogramming wiki, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.chessprogramming.org/Connection_Machine ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Architecture and applications of the Connection Machine - cs.wisc.edu, accessed November 18, 2025, https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~markhill/restricted/computer88_cm2.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10

-

“The Design of the Connection Machine” - Article in DesignIssues Journal, Tamiko Thiel. Artificial intelligence parallel programming supercomputer design., accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.tamikothiel.com/theory/cm_txts/index.html ↩

-

Commodity computing - Wikipedia, accessed October 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodity_computing ↩

-

Connection Machine CM-5 Technical Summary - MIT CSAIL, accessed November 19, 2025, https://people.csail.mit.edu/bradley/cm5docs/nov06/ConnectionMachineCM-5TechnicalSummary1993.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14

-

CM-2 | PSC - Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.psc.edu/resources/cm-2/ ↩