1.5 Amdahl's Law and Gustafson's Law

The transition to parallel computing raises a question: how much performance improvement, or speedup, can be achieved by adding more processors? It might be expected that using N processors would make a program run N times faster. However, the reality is more complex. Two foundational laws, Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law, provide theoretical frameworks for answering this question. They offer different, and seemingly contradictory, perspectives on the potential of parallelization, stemming from their different underlying assumptions about the nature of the problem being solved.

Amdahl’s Law: The Law of Diminishing Returns (Strong Scaling)

Section titled “Amdahl’s Law: The Law of Diminishing Returns (Strong Scaling)”Developed by computer architect Gene Amdahl in 1967, Amdahl’s Law provides a formula for the theoretical maximum speedup of a task when its resources are improved 1. It was used as an argument against the feasibility of massively parallel processing, as it highlights a limit to the benefits of parallelization 2.

Core Assumption

Section titled “Core Assumption”The law is based on the assumption of a fixed problem size. The goal is to solve the same computational workload, but faster. This performance model is known as strong scaling 32.

The Serial Fraction

Section titled “The Serial Fraction”Amdahl’s Law recognizes that any program can be divided into two parts: a fraction that is parallelizable and a fraction that is inherently sequential and must be executed on a single processor. This sequential part includes tasks like program initialization, I/O operations, and parts of the algorithm that have data dependencies preventing parallel execution.

Formula

Section titled “Formula”The speedup of a program is limited by this serial fraction, denoted as (or ). The formula for speedup with processors is:

Where is the proportion of the program’s execution time that is serial, and is the proportion that is parallelizable 3.

Implication

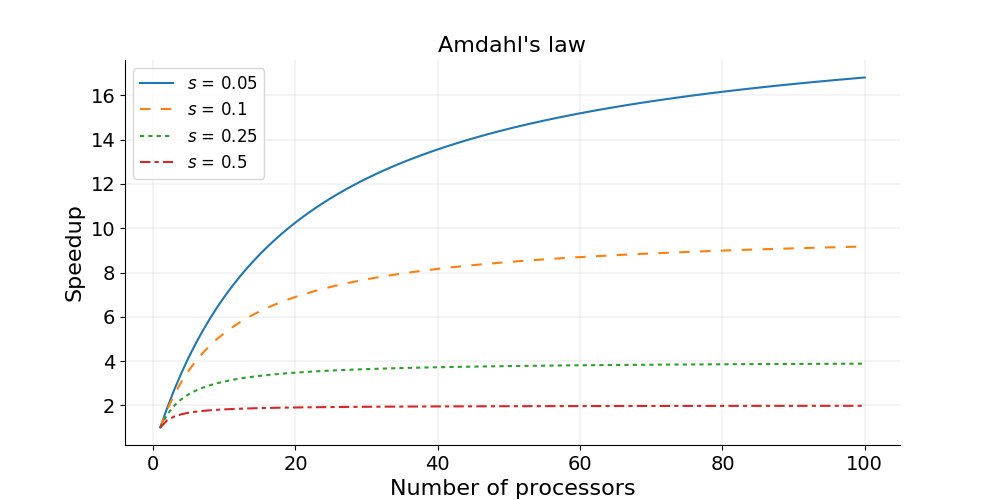

Section titled “Implication”The key implication of this formula is that as the number of processors () approaches infinity, the term approaches zero. The maximum possible speedup is therefore capped at 4. This presents a constrained view of parallelism. For example, if a program has 10% of its code that is inherently serial (), the maximum achievable speedup is , regardless of whether 100 or 1,000,000 processors are used. This “law of diminishing returns” suggests that the serial portion of a program will always be the ultimate bottleneck, limiting the potential of massively parallel systems.

Amdahl’s Law visualization showing how speedup plateaus as the number of processors increases, with the ceiling determined by the serial fraction. Image by Xin Li via KTH PDC Blog

Gustafson’s Law: Scaled Speedup (Weak Scaling)

Section titled “Gustafson’s Law: Scaled Speedup (Weak Scaling)”In 1988, John Gustafson, working on massively parallel supercomputers at Sandia National Laboratories, observed that the constraints described by Amdahl’s Law did not align with empirical performance results. He proposed a different perspective, now known as Gustafson’s Law (or Gustafson–Barsis’s Law), which provides an alternative perspective for large-scale parallelism 1.

Core Assumption

Section titled “Core Assumption”Gustafson’s Law operates under the assumption that the problem size scales with the number of processors. The goal is not to do the same work faster, but to perform more work in the same amount of time 3. This is common in scientific computing, where having more computational power allows researchers to run simulations with higher resolution, more particles, or for longer durations. This performance model is known as weak scaling 5.

Revisiting the Serial Fraction

Section titled “Revisiting the Serial Fraction”The law assumes that the amount of time spent in the serial part of a program remains constant, regardless of the problem size, while the parallelizable part of the workload grows proportionally with the number of processors 3.

Formula

Section titled “Formula”The formula for this “scaled speedup” is commonly written as:

Where is the fraction of time spent in the serial portion of the program on the parallel system, and is the number of processors 3.

Implication

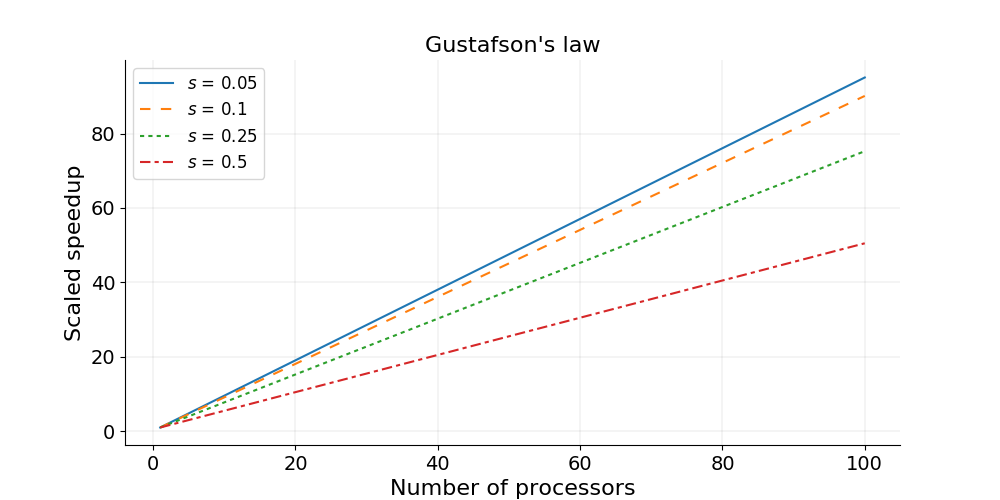

Section titled “Implication”This formula shows a linear relationship between the number of processors and the achievable speedup. If the serial fraction is small, the speedup is approximately . This suggests that for problems that can scale their workload, there is no theoretical upper limit to the speedup that can be achieved by adding more processors. This provided a theoretical justification for building massively parallel machines, as it aligned with the goal of using more computational resources to solve larger problems 6.

Gustafson’s Law visualization showing near-linear speedup growth with increasing processors when problem size scales accordingly. Image by Xin Li via KTH PDC Blog

Synthesizing the Two Laws

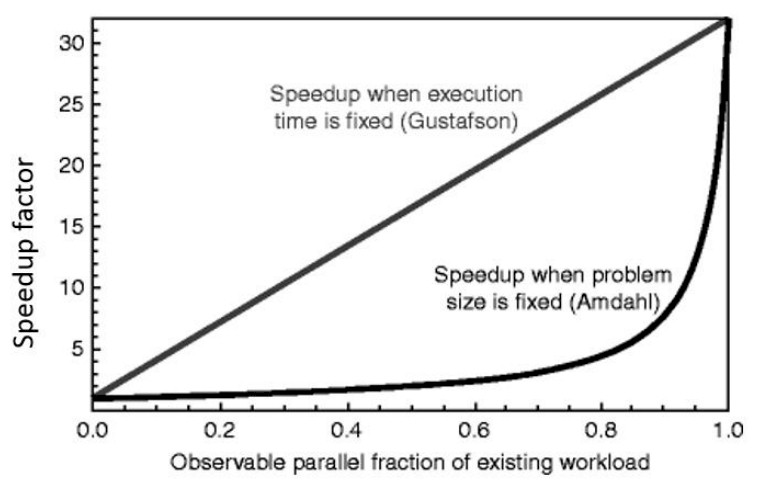

Section titled “Synthesizing the Two Laws”The apparent contradiction between Amdahl’s and Gustafson’s laws led to considerable debate. However, a careful analysis reveals that they are not contradictory, but are mathematically equivalent formulations representing two different perspectives on performance, stemming from different assumptions and definitions 27.

The primary difference is the reference frame used to define the serial fraction .

- Amdahl’s Law defines as a fraction of the total execution time on a single processor. It is a fixed characteristic of the algorithm for a given problem size.

- Gustafson’s Law defines as a fraction of the total execution time on the parallel system with processors. As the problem size scales with , the total amount of parallel work grows, making the fixed amount of serial work a smaller and smaller proportion of the total execution time.

Therefore, the choice of which law is more relevant depends entirely on the goals and constraints of the computational problem at hand:

Strong Scaling (Amdahl’s Law)

Section titled “Strong Scaling (Amdahl’s Law)”This is the relevant metric for problems where the total problem size is fixed and the primary goal is to reduce the time to solution (latency). This is critical for applications like real-time transaction processing, weather forecasting where a deadline must be met, or user-facing interactive applications.

Weak Scaling (Gustafson’s Law)

Section titled “Weak Scaling (Gustafson’s Law)”This is the relevant metric for problems where the amount of work can be expanded to take advantage of more computational resources. The goal is to increase the problem’s scale or fidelity (throughput) while keeping the execution time constant. This applies to scientific simulations, high-resolution computer graphics rendering, and large-scale data analysis 5.

The historical context of this debate reflects an evolution in computing goals. Amdahl’s Law, from 1967, emerged from a mainframe-centric era focused on accelerating existing, well-defined business and computational tasks. Gustafson’s Law, from 1988, originated from national laboratory supercomputing, where the availability of more processing power did not just mean obtaining results faster, but also addressing new and larger-scale scientific problems—to analyze data “more carefully and fully” 6. The shift from an Amdahl-centric to a Gustafson-centric view of performance mirrors the evolution of high-performance computing from a tool for accelerating calculations to a tool for scientific discovery and large-scale data exploration.

Direct comparison of Amdahl’s Law (fixed problem size) and Gustafson’s Law (fixed execution time) showing how speedup varies with the parallel fraction of the workload. Image by Timothy Prickett Morgan via The Next Platform

Comparison of Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law

Section titled “Comparison of Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law”| Feature | Amdahl’s Law | Gustafson’s Law |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | Problem size is fixed. | Problem size scales with the number of processors. |

| Perspective on Problem Size | The goal is to solve the same problem in less time. | The goal is to solve a larger problem in the same amount of time. |

| Definition of Serial Fraction () | Proportion of runtime on a single processor. | Proportion of runtime on the parallel system. |

| Speedup Focus | Strong Scaling (Time-constrained). | Weak Scaling (Problem-constrained). |

| Formula | ||

| Implication for Max Speedup | As , Speedup is limited to . | Speedup grows linearly with ; no theoretical upper limit. |

| Primary Application Context | Real-time systems, latency-sensitive applications. | Scientific simulation, big data analysis, high-fidelity modeling. |

References

Section titled “References”Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law | PDF | Parallel Computing - Scribd, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/presentation/68721034/Amdahl-s-Law-and-Gustafson-s-law ↩ ↩2

-

Reevaluating Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law - Temple CIS, accessed September 30, 2025, https://cis.temple.edu/~shi/wwwroot/shi/public_html/docs/amdahl/amdahl.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

The Performance of Parallel Algorithms by Amdahl’s Law …, accessed September 30, 2025, http://www.ijcsit.com/docs/Volume%202/vol2issue6/ijcsit2011020660.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

en.wikipedia.org, accessed September 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallel_computing ↩

-

Amdahl’s Law VS Gustafson’s Law - Lei Mao’s Log Book, accessed September 30, 2025, https://leimao.github.io/blog/Amdahl-Law-VS-Gustafson-Law/ ↩ ↩2

-

Gustafson’s law - Wikipedia, accessed September 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustafson%27s_law ↩ ↩2

-

(PDF) Reevaluating Amdahl’s law and Gustafson’s law - ResearchGate, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228367369_Reevaluating_Amdahl%27s_law_and_Gustafson%27s_law ↩