1.3 Defining Parallel Computing

The physical and architectural limitations inherent in the serial computing model—the power constraints that ended frequency scaling and the performance bottlenecks of the von Neumann bottleneck and Memory Wall—necessitated a shift in computer architecture. This shift was towards parallel computing, a paradigm that defines the modern era of high-performance computing and is now ubiquitous across devices, from smartphones to supercomputers 1.

The Fundamental Concept

Section titled “The Fundamental Concept”Fundamentally, parallel computing is a type of computation in which many calculations or processes are carried out simultaneously 1. It contrasts with the serial computing model, which dictates that instructions are executed sequentially, one after another, on a single processor 2.

The core principle of parallel computing is decomposition 2. A large, complex computational problem is broken down into smaller, discrete parts that can be solved concurrently 2. Each of these smaller parts is then assigned to a different processing element, which executes its portion of the algorithm simultaneously with the others 2. Finally, a coordination mechanism combines the individual results into a final solution 2.

For a problem to be suitable for parallel computing, it must exhibit characteristics that allow for this decomposition. It must be divisible into pieces of work that can be solved simultaneously, and the total time to solution must be less with multiple compute resources than with a single one 2.

The Imperative for Parallelism: The End of Frequency Scaling

Section titled “The Imperative for Parallelism: The End of Frequency Scaling”For several decades, the primary method for increasing computer performance was frequency scaling—increasing the clock speed of a single processor to make it execute its serial instruction stream faster. This approach provided a significant benefit to software developers; their existing programs would automatically run faster on each new generation of hardware without any modification 1.

However, in the early 2000s, this strategy encountered a significant physical barrier known as the power wall 3. The power consumed by a processor is directly related to its clock frequency 3. As frequencies climbed into the multiple gigahertz range, power consumption and heat generation increased substantially 3. It became technologically and economically infeasible to dissipate the substantial heat produced by these high-frequency single-core processors 3.

Faced with this wall, the semiconductor industry changed its strategy. Instead of trying to build a single, faster core, manufacturers began using the increasing number of transistors available on a chip (as predicted by Moore’s Law) to place multiple, simpler, and more power-efficient processing cores on a single die 3. This marked the introduction of multi-core processors (dual-core, quad-core, etc.) and established parallel computing as the dominant paradigm in all areas of computer architecture, from mobile devices to massive data centers 1.

This shift had a significant impact on the software industry. To take advantage of the performance potential of new hardware, software now had to be explicitly designed and written to be parallel. This required a fundamental change in algorithm design and introduced a set of new challenges for programmers. Issues such as task decomposition, load balancing (ensuring an equitable distribution of work among processors), communication between processors, and synchronization (coordinating access to shared resources to avoid data corruption) became primary concerns in software engineering. This transition from implicit performance gains through hardware speed to explicit performance gains through parallel software design represents a significant paradigm shift in computing.

Forms of Parallel Architecture

Section titled “Forms of Parallel Architecture”Parallel computers are built using several different hardware architectures, which can be broadly classified based on how their processors access memory 2.

Shared Memory Systems

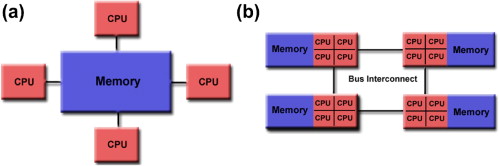

Section titled “Shared Memory Systems”In this architecture, multiple processors or cores are contained within a single machine and are all connected to a single, globally accessible main memory 4. Any processor can directly access any memory location. This model simplifies programming, as processors communicate implicitly by reading and writing to the same memory locations. Most modern multi-core laptops, desktops, and smartphones are examples of shared memory parallel computers 2.

Basic shared memory architecture. (a) Uniform memory access (UMA) architecture. (b) Non-uniform memory access (NUMA) architecture. Image Credit: ScienceDirect

Distributed Memory Systems

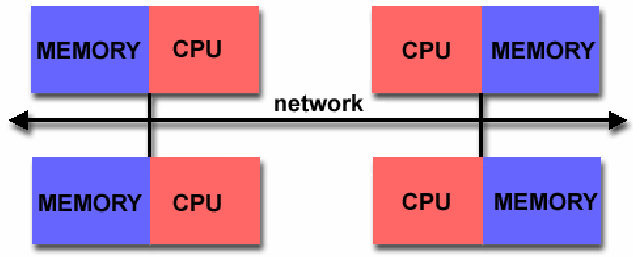

Section titled “Distributed Memory Systems”This architecture connects multiple independent computers, often called nodes, via a high-speed network 2. Each node contains its own processor(s) and its own private, local memory. A processor in one node cannot directly access the memory of another node. Therefore, communication and data sharing must be handled explicitly by the programmer, typically by sending and receiving messages over the network 2. This model is highly scalable and forms the basis of most large-scale supercomputer clusters and cloud computing infrastructures 4.

A typical distributed memory architecture where each processor has its own private memory, and communication is handled over a network. Image Credit: ResearchGate

Hybrid Systems

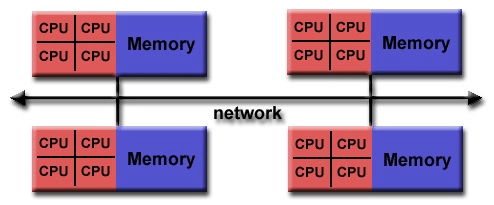

Section titled “Hybrid Systems”Modern high-performance computing (HPC) systems commonly use a hybrid architecture of the shared and distributed memory models 5. These systems are clusters of multiple nodes connected by a network (a distributed memory system). However, each individual node is itself a shared memory parallel computer, containing multiple cores that share access to that node’s local memory 2. This hierarchical design allows programmers to use shared-memory programming techniques within a node and message-passing techniques for communication between nodes, offering a balance of programming convenience and scalability.

A hybrid distributed-shared memory architecture where multiple nodes (each with multiple CPUs and shared memory) are connected via a network, combining both shared memory within nodes and distributed memory across nodes. Image Credit: ResearchGate

References

Section titled “References”Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

en.wikipedia.org, accessed September 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallel_computing ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Introduction to Parallel Computing Tutorial - | HPC @ LLNL, accessed September 30, 2025, https://hpc.llnl.gov/documentation/tutorials/introduction-parallel-computing-tutorial ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11

-

The von Neumann Architecture — UndertheCovers - Jonathan Appavoo, accessed September 30, 2025, https://jappavoo.github.io/UndertheCovers/textbook/assembly/vonNeumannArchitecture.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Parallel Computing And Its Modern Uses | HP® Tech Takes, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.hp.com/us-en/shop/tech-takes/parallel-computing-and-its-modern-uses ↩ ↩2

-

What is parallel computing? | IBM, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/parallel-computing ↩