1.2 The von Neumann Bottleneck and the Memory Wall

For decades, the performance of computers based on the von Neumann architecture improved at an exponential rate, primarily by increasing the clock speed of the CPU, allowing the fetch-decode-execute cycle to run faster. However, this approach eventually encountered fundamental physical and architectural limits. The very design that made the von Neumann architecture so successful—its centralized processing and unified memory system—contains inherent structural flaws that become increasingly problematic as the performance gap between components widens. These limitations manifest as two distinct but interconnected challenges: the von Neumann bottleneck and the Memory Wall. Together, they became the primary motivation for the paradigm shift towards parallel computing.

Defining the von Neumann Bottleneck

Section titled “Defining the von Neumann Bottleneck”The von Neumann bottleneck is a fundamental throughput limitation imposed by the architecture’s reliance on a single, shared communication pathway (the system bus) between the CPU and main memory 1. This shared bus must be used for two distinct purposes: fetching program instructions and transferring data for processing 1. Because these two operations cannot occur at the same time, they create a traffic congestion that constrains the overall performance of the system.

The CPU, capable of executing billions of operations per second, frequently experiences delays awaiting information. It must constantly shuttle instructions and data back and forth across this relatively narrow bus. This forces the high-speed processor to frequently stall, entering idle wait states while it waits for the next instruction or data value to arrive from the much slower main memory 2. This wasted time represents a significant loss of potential computational power. The bottleneck is, therefore, fundamentally a bandwidth problem: the “pipe” connecting the processor and memory is too narrow to keep up with the processor’s demand for information 34.

Defining the Memory Wall

Section titled “Defining the Memory Wall”The Memory Wall is a related but distinct performance problem, first articulated in a seminal 1994 paper by William Wulf and Sally McKee, that arises from the diverging rates of performance improvement between processors and memory 35. While processor performance was historically improving at roughly 60% per year, the latency of Dynamic Random-Access Memory (DRAM) was only improving at about 7% per year 3. Because the difference between two diverging exponential functions is itself an exponential, this created an exponentially widening gap in relative performance.

Image Credit: ResearchGate/Christine Eisenbeis. A visual representation of the growing disparity between CPU performance improvement and memory (DRAM) performance improvement over the years. The widening gap is often referred to as the “Memory Wall.”

This growing disparity means that the cost of accessing memory, measured in terms of lost CPU cycles, has increased dramatically. In the early days of computing, CPU and memory speeds were relatively balanced. Today, a modern CPU can execute hundreds or even thousands of instructions in the time it takes to complete a single read from main memory. The Memory Wall is, therefore, fundamentally a latency problem: the “pipe” connecting the processor and memory is not only narrow but also very long, and the time it takes for data to travel that length is becoming prohibitively expensive 3.

The von Neumann bottleneck and the Memory Wall are not the same phenomenon, but they create a compounding crisis that severely limits system performance. The latency problem of the Memory Wall means each memory access is costly in terms of time. The bandwidth problem of the von Neumann bottleneck means the number of these accesses that can happen concurrently is limited. A faster CPU, which exacerbates the Memory Wall by being able to perform more work between memory accesses, also places a higher demand on the system bus, thereby intensifying the bottleneck. This creates a feedback loop where improvements in processing power yield diminishing returns because the data pathway cannot keep up. This interconnected dynamic is the primary reason why simply making single-core CPUs faster ceased to be a viable strategy for increasing overall system performance.

Consequences and Modern Workloads

Section titled “Consequences and Modern Workloads”The combined impact of these issues is particularly acute for modern, data-intensive workloads. Applications in fields like Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and big data analytics are characterized by their need to process enormous datasets 2. Training a large neural network, for example, can involve continuously moving billions or even trillions of model parameters (weights) between memory and the processing units 2. In such scenarios, the system spends the vast majority of its time and energy not on computation, but on shuttling data across the bottleneck 6.

This data movement is also extremely costly in terms of energy. The energy required to move a piece of data from DRAM to the CPU can be orders of magnitude greater than the energy required to perform a floating-point operation on that data 2. As a result, the von Neumann architecture is fundamentally inefficient for these tasks, leading to substantial energy consumption and acting as a major impediment to progress in AI computing 2.

Architectural Mitigations

Section titled “Architectural Mitigations”To combat the von Neumann bottleneck and the Memory Wall, computer architects have developed a range of sophisticated techniques that modify the pure von Neumann design. These mitigations are now standard in virtually all modern computers:

Memory Hierarchy (Caches)

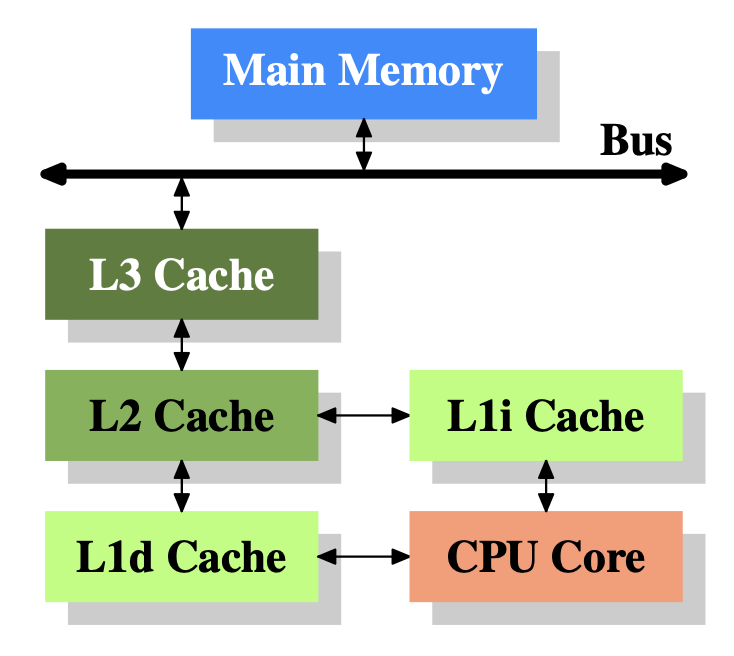

Section titled “Memory Hierarchy (Caches)”The most effective and widely used strategy is the introduction of a memory hierarchy. This involves placing one or more levels of small, fast, and expensive cache memory (typically Static RAM or SRAM) between the CPU and the large, slow, and cheap main memory (DRAM) 1. Caches exploit the principle of locality—the tendency of programs to access the same data and instructions repeatedly in a short period. By storing frequently used information in the cache, the CPU can access it much more quickly, avoiding the long latency of a main memory access. Modern systems employ multiple levels of cache (L1, L2, L3), each larger and slower than the last, creating a tiered system to buffer the CPU from memory latency 4.

Modified Harvard Architecture

Section titled “Modified Harvard Architecture”While a pure von Neumann machine uses a single bus for everything, most modern high-performance CPUs implement a modified Harvard architecture at their core 1. This involves using separate L1 caches for instructions (I-cache) and data (D-cache), each with its own dedicated access path to the CPU’s execution units 1. This separation allows the CPU to fetch an instruction and load or store data simultaneously, directly alleviating the von Neumann bottleneck at the level closest to the processor. The system as a whole still maintains a unified main memory, hence the term “modified” Harvard architecture.

Image Credit: Based on a diagram from “What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory” by Ulrich Drepper.

Advanced CPU Features

Section titled “Advanced CPU Features”Modern CPUs employ a host of other techniques to hide memory latency and improve throughput, including:

- Pipelining: Overlapping the fetch, decode, and execute stages of multiple instructions.

- Out-of-Order Execution: Allowing the CPU to execute instructions as soon as their operands are ready, rather than in strict program order.

- Speculative Prefetching: Intelligently guessing which data and instructions the program will need next and loading them into the cache ahead of time 4.

Processing-in-Memory (PIM) and Near-Memory Computing

Section titled “Processing-in-Memory (PIM) and Near-Memory Computing”A more radical and forward-looking approach aims to eliminate the bottleneck by fundamentally rethinking the separation of processing and memory. PIM proposes moving some computational capabilities directly into the memory unit itself 7. This would allow simple operations to be performed on data where it resides, avoiding the costly and energy-intensive data transfer to the CPU. This is an active area of research, leveraging emerging memory technologies like memristors, Resistive RAM (RRAM), and 3D-stacked memory to create architectures that are far more efficient for data-intensive tasks 3.

References

Section titled “References”Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Von Neumann architecture - Wikipedia, accessed September 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann_architecture ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

How the von Neumann bottleneck is impeding AI computing - IBM …, accessed September 30, 2025, https://research.ibm.com/blog/why-von-neumann-architecture-is-impeding-the-power-of-ai-computing ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

mMPU – a Real Processing–in–Memory Architecture to … - ASIC2, accessed September 30, 2025, https://asic2.group/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/mMPU_Springer_final.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Motivation Von-Neumann Bottleneck Mitigation Performance Walls, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.cse.wustl.edu/~roger/560M.f23/CSE560-DomainSpecificAccelerators.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Hitting the Memory Wall: Implications of the Obvious - LibraOpen, accessed October 1, 2025, https://libraopen.lib.virginia.edu/downloads/4b29b598d ↩

-

Future of Memory: Massive, Diverse, Tightly Integrated with Compute – from Device to Software - DAM, accessed September 30, 2025, https://dam.stanford.edu/papers/liu24iedm.pdf ↩

-

(PDF) Von Neumann Architecture and Modern Computers. - ResearchGate, accessed September 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236141703_Von_Neumann_Architecture_and_Modern_Computers ↩